ITMA Barcelona Spain 2019 Specialyarns

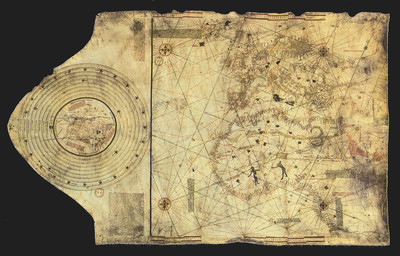

Under the Mongol Empire's hegemony over Asia (the Pax Mongolica, or Mongol peace), Europeans had long enjoyed a safe land passage, the Silk Road, to the Indies (then construed roughly as all of south and east Asia) and China, which were sources of valuable goods such as spices and silk. With the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the land route to Asia became much more difficult and dangerous. Portuguese navigators tried to find a sea way to Asia. In 1470, the Florentine astronomer Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli suggested to King Afonso V of Portugal that sailing west would be a quicker way to reach the Spice Islands, Cathay, and Cipangu than the route around Africa. Afonso rejected his proposal] Portuguese explorers, under the leadership of King John II, then developed the Cape Route to Asia around Africa. Major progress in this quest was achieved in 1488, when Bartolomeu Dias reached the Cape of Good Hope, in what is now South Africa. Meanwhile, in the 1480s, the Columbus brothers had picked up Toscanelli's suggestion and proposed a plan to reach the Indies by sailing west across the "Ocean Sea", i.e., the Atlantic. However, Dias's discovery had shifted the interests of Portuguese seafaring to the southeast passage, which complicated Columbus's proposals significantly. Between 1492 and 1503, Columbus completed four round-trip voyages between Spain and the Americas, all of them under the sponsorship of the Crown of Castile. These voyages marked the beginning of the European exploration and colonization of the American continents, and are thus of enormous significance in Western history.

Between 1492 and 1503, Columbus completed four round-trip voyages between Spain and the Americas, all of them under the sponsorship of the Crown of Castile. These voyages marked the beginning of the European exploration and colonization of the American continents, and are thus of enormous significance in Western history

Ruta de la Seda

"Ruta de la Seda" fue creado por el geógrafo alemán Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen, quien lo introdujo en su obra Viejas y nuevas aproximaciones a la Ruta de la Seda, en 1877. Debe su nombre a la mercancía más prestigiosa que circulaba por ella, la seda, cuya elaboración era un secreto que solo los chinos conocían. Los romanos (especialmente las mujeres de la aristocracia) se convirtieron en grandes aficionados de este tejido, tras conocerlo antes del comienzo de nuestra era a través de los partos, quienes se dedicaban a su comercio. Muchos productos transitaban estas rutas: piedras y metales preciosos (diamantes de Golconda, rubíes de Birmania, jade de China, perlas del golfo Pérsico), telas de lana o de lino, ámbar, marfil, laca, especias, porcelana, vidrio, materiales manufacturados, coral, La Ruta de la Seda dio origen a agrupaciones de estados militares originarios del norte de China, abriendo el Asia central y China a religiones como el nestorianismo, maniqueísmo, budismo, y más tarde islamismo, y creando la influyente Federación de Jazaria, que al final de su gloria trajo el mayor imperio continental que existió nunca: el Imperio mongol, con sus centros políticos encadenados a lo largo de la Ruta de la Seda (Pekín, en el norte de China; Karakorum, en el centro de Mongolia; Samarcanda, en Transoxiana; Tabriz, en el norte de Irán; Sarai y Astracán, en el curso del Bajo Volga; Solkhat, en Crimea; Kazán, en Rusia central; y Erzurum, en el este de Anatolia), realizando la unificación política de zonas anteriormente libres y conectadas de forma intermitente por bienes materiales y culturales. En Asia central, el islam se expandió a partir del siglo VII, haciendo un alto en su progresión hacia el occidente chino tras la batalla de Talas en el año 751. Los túrquicos islámicos siguieron la expansión a partir del siglo X, lo que terminó por perturbar el comercio en esa parte del mundo, y acarreando la casi desaparición del budismo. Durante gran parte de la Edad Media, el Califato islámico (centrado en el Cercano Oriente) tuvo a menudo el monopolio sobre gran parte del comercio realizado a través del Viejo Mundo.

Agreement with the Spanish crown The Flagship of Columbus and the Fleet of Columbus 400th Anniversary Issues of 1893 U.S. stamps reflecting the most commonly held view as to what Columbus's first fleet might have looked like. The Santa María, the flagship of Columbus's fleet, was a carrack—a merchant ship of between 400 and 600 tons, 75 feet (23 m) long, with a beam of 25 feet (7.6 m), allowing it to carry more people and cargo. It had a deep draft of 6 feet (1.8 m). The vessel had three masts: a mainmast, a foremast, and a mizzenmast. Five sails altogether were attached to these masts. Each mast carried one large sail. The foresail and mainsail were square; the sail on the mizzen was a triangular sail known as a lateen mizzen. The ship had a smaller topsail on the mainmast above the mainsail and on the foremast above the foresail. In addition, the ship carried a small square sail, a spritsail, on the bowsprit. After continually lobbying at the Spanish court and two years of negotiations, he finally had success in January 1492. Ferdinand and Isabella had just conquered Granada, the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian Peninsula, and they received Columbus in Córdoba, in the Alcázar castle. Isabella turned him down on the advice of her confessor. Columbus was leaving town by mule in despair when Ferdinand intervened. Isabella then sent a royal guard to fetch him, and Ferdinand later claimed credit for being "the principal cause why those islands were discovered